Evidence-based legislation refers to using the best available scientific evidence and systematically collected data to formulate and draft laws.

“Evidence-based policymaking uses the best available research and data on program results to inform government budget, policy, and management decisions. It focuses on what works—those programs that rigorous evaluations have shown to achieve positive outcomes.

By using this approach, governments can:

- Reduce wasteful spending. Targeting funding based on evidence of effectiveness enables policymakers to identify and eliminate programs that have failed to deliver expected results, freeing dollars for other uses.

- Expand successful programs. Comparing programs allows policymakers to direct funding to those that deliver the highest return on investment.

- Strengthen accountability. Focusing on outcomes makes it easier to hold agencies, managers, and providers accountable for results.”1

9.1 Democracy Index of the Economist Intelligent Unit

The Democracy Index is an index measuring democracy compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit of the Economist Group, a UK-based private company that publishes the weekly newspaper The Economist. Similarly to other democracy indices, such as V-Dem Democracy indices or the Bertelsmann Transformation Index, it attempts to measure the state of democracy and is centrally concerned with political institutions and freedoms.

The Democracy Index is a valuable tool for assessing the state of democracy around the world, as it provides a comprehensive and objective measure of democracy. Such a tool is important to track the evolution of democratic parameters over time. This tool is important for policymakers and activists to identify countries where democracy is under threat and to develop strategies to support it.

The index includes 167 countries and territories, of which 166 are sovereign states, and 164 are UN Member States. The index is based on 60 indicators grouped into five categories, measuring pluralism, civil liberties, and political culture. In addition to a numeric score and a ranking, the index categorizes each country into one of four regime types: full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes, and authoritarian regimes.

In 2022, the Democracy Index classified 57 countries as full democracies, 61 countries as flawed democracies, 35 countries as hybrid regimes, and 59 countries as authoritarian regimes.

Some of the key findings of the 2022 Democracy Index are:

- Ukraine’s example for democracy. A focus of this year’s Democracy Index report is Russia’s war in Ukraine and its importance for the future of democracy in Europe and globally. The commitment of the Ukrainian people to fight for the right to decide their own future is inspiring. It shows the power of democratic ideas and principles to bind together a nation and its people in the pursuit of democracy.

- Russia: the biggest loser in 2022. If Ukraine’s fight to defend its borders is a demonstration of democracy in action, Russia’s violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty is the product of an imperial mindset (an “empire state of mind”). Vladimir Putin’s dream of restoring Russia’s position as an imperial power is foundering. After more than ten months of fighting in Ukraine, it was clear by the end of 2022 that Russia was not only losing on the battlefield but also struggling to win the propaganda war at home and abroad.

- Room at the top: the Nordics and Europe dominate. The Nordics (Norway, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, and Denmark) dominate the top tier of the Democracy Index rankings, taking five of the top six spots, with New Zealand claiming second place. Norway remains the top-ranked country in the Democracy Index, thanks to its high scores across all five categories of the index, especially electoral process and pluralism, political culture, and political participation.

- The best and the worst of 2022: upgrades, downgrades, and regime changes. Unsurprisingly, in a year characterized by inertia in the Democracy Index global score, there are few changes in regime classification in 2022—five, compared with 13 in 2021. Chile, France, and Spain moved up to the “full democracy” category, while Papua New Guinea and Peru have been downgraded from “flawed democracies” to “hybrid regimes.” These countries are not the best and worst performers in terms of their score changes, however. Thailand tops the world for the biggest score increase (+0.62) as the space for political opposition opened up and the insurgency threat to the country receded. At the opposite end of the spectrum, close behind Russia (-0.96) in terms of score regressions, are Burkina Faso (-0.76), Haiti (-0.68) and El Salvador (-0.66).

- Drug traffickers, insurgents, warlords, cyber hackers, and other threats to sovereignty and democracy. Threats to national sovereignty come not only from invading armies such as Russia’s but also from non-state actors such as drug-trafficking groups, private armies, Islamists and other insurgencies, and hackers committing cyber-attacks. Powerful drug cartels in Latin America and the Caribbean challenge state control over territory and are corrosive of national institutions, as well as threatening the security of ordinary citizens. This problem has exacerbated already high levels of corruption in the region and is eroding democratic norms in many countries. In many parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, especially the Sahel and West Africa, the writ of the state no longer runs across the country as militant Islamist groups establish control over territory and terrorize the inhabitants. This power vacuum has sometimes resulted in outside powers, often former colonial powers, providing military and other assistance to governments.”2

9.2 Democracy Tracker

The Democracy Tracker is part of the International IDEA Global State of Democracy Initiative. It provides event-centric, monthly information on democracy and human rights developments in 173 countries. Event reports include a description of the event, indications of the specific aspects of democracy that have been impacted, the magnitude of the impact, links to original sources, and keywords to enable further research.

According to the 2023 Report of The Global State of Democracy, titled The New Checks and Balances:

- Over the past five years, half of all countries saw declines in at least one indicator.

- Net declines outnumbered net advances for the sixth consecutive year.

- Broad declines were in representation, rights, and rule of law worldwide.

- There were limited improvements in the fight against corruption in Latin America, Asia, and Europe.

- Courts and regulatory bodies have stepped in where executive and legislatures have weakened.

- The continued engagement of people will continue driving progress.

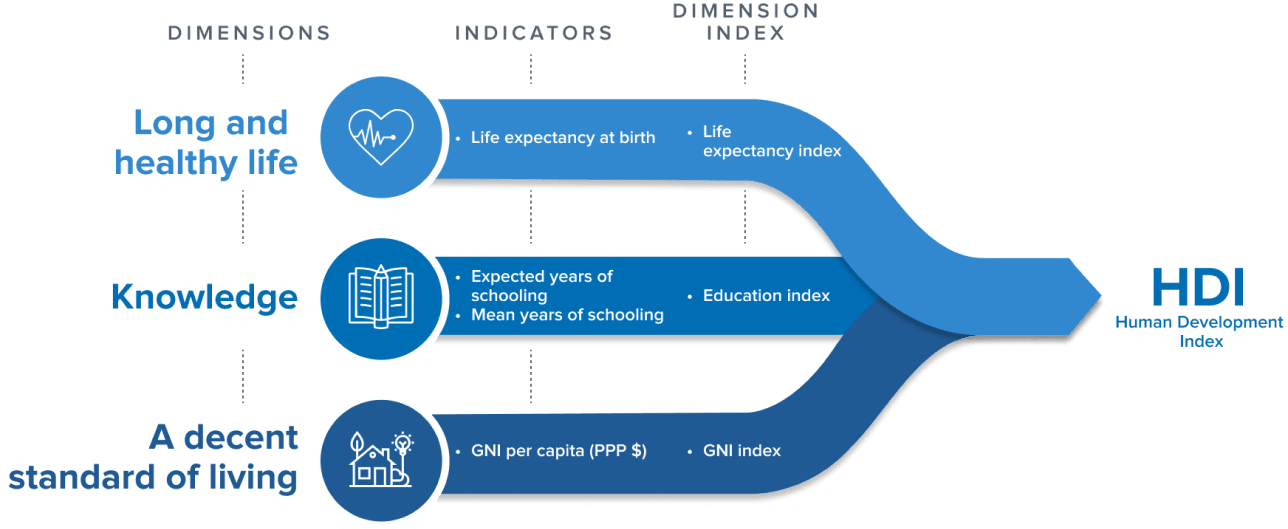

9.3 The Human Development Indicator (HDI)

The HDI was created to emphasize that people and their capabilities should be the ultimate criteria for assessing the development of a country, not economic growth alone. The HDI was introduced in 1990, and it is a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development:

- Longevity

- Education

- Income

HDI Dimensions and Indicators

9.4 Twin indices on women’s empowerment and gender equality

The Women’s Empowerment Index (WEI) evaluates women's and girl’s achievement in expanding their capabilities across five dimensions to make choices and seize opportunities in life:

- Life and good health;

- Education, skill building, and knowledge;

- Labor and financial inclusion;

- Participation in decision-making; and

- Freedom from violence.

The Global Gender Parity Index (GGPI) assesses the status of women relative to that of men in the first four dimensions, with some variation in indicators and variable treatment. Some of the key findings of the GGPI are:

- “Globally, women are empowered to achieve, on average, only 60 percent of their full potential, as measured by the WEI and achieve, on average, 28 percent less than men across key human development dimensions, as measured by the GGPI.

- None of the 114 countries analysed has achieved full women’s empowerment or complete gender parity. Moreover, less than 1 percent of women and girls live in countries with both high women’s empowerment and high performance in achieving gender parity.

- 3.1 billion women and girls - more than 90 percent of the world’s female population - live in countries characterized by low or middle women’s empowerment and low or middle performance in achieving gender parity.

- About 8 percent of women and girls live in countries with low or middle women’s empowerment but high performance in achieving gender parity. This suggests that small gender gaps do not automatically translate into high women’s empowerment.

- No country has achieved high women’s empowerment while maintaining a large gender gap. This suggests that women and girls’ empowerment will remain elusive until gender gaps are eliminated.

- Higher human development alone is insufficient to empower women and girls and bring about gender equality. Of the 114 countries analyzed, 85 have low or middle women’s empowerment and low or middle performance in achieving gender parity. More than half the countries in this group are in the high 1. Overview 1 (21 countries) or very high human development group (26 countries), signifying that higher human development does not automatically translate into women’s empowerment and gender equality.

- The WEI and GGPI offer different but complementary lenses for assessing progress in advancing women’s human development, power, and freedoms. In isolation, each provides only a partial picture of progress. Together, they shed light on the complex challenges faced by women worldwide and pave the way for targeted interventions and policy reforms.”3

9.5 New Initiative: United Nations Special Rapporteur on Democracy

“For the sixth year in a row, a majority of countries experienced declining rule of law, driven by two sets of issues—authoritarian trends (measured by the Index factors on Constraints on Government Powers and Fundamental Rights) and struggling justice systems (measured by the Index factors on Civil and Criminal Justice). More than six billion people—76% of the world’s population–live in countries where the rule of law weakened in the past year.”4

Given the situation of democratic backsliding worldwide, Democracy Without Borders (DWB) is spearheading a project to galvanize broad support for the creation of a new mandate established by the Human Rights Council: that of a UN Special Rapporteur on Democracy (UNRoD).5 The mandate of a Special Rapporteur will be dedicated to investigating democratic rights and institutions and their development. Parliamentarians for Global Action support the establishment of such a mandate.

Footnotes:

1 Pew Charitable Trusts and MacArthur Foundation, Legislating Evidence-Based Policymaking.

2 Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2022 Frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine

3 UN Women and UNDP, THE PATHS TO EQUAL Twin indices on women’s empowerment and gender equality

4 World Justice Project, Rule of Law Index, October 25, 2023.

5 Maartje Mensink, A UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON DEMOCRACY On the possibility of a new mandate under the United Nations Human Rights Council.